The essay below is my submission to the STSC Symposium, a monthly set-theme collaboration between STSC writers. The topic this month is Dinosaurs.

When Jack Grealish was four he loved two things and two things only. They populated his whole existence in an on-off way: if football was on, dinosaurs were off and vice versa. Rarely did one bleed into the other, rarely did he manage to find eleven stegosaurus figures to line up on the living room floor against the formidable Premier League champions of dinosaur football: T. Rex United. As a rule it was either his obsession with dinosaurs or football that was running his life.

If you don’t know who Jack Grealish is, he is a famousfootballer who was, until a month ago, the most expensive player in English football when Manchester City bought him for £100 million in the summer of 2021 from his boyhood club Aston Villa.

Footballers, on the whole, have a reputation for being unintelligent, and Jack Grealish lives up to the stereotype in fine fashion. If you don’t know who Aston Villa are, they are a Premier League football club from Birmingham, and if you don't know where Birmingham is on a map, don't worry, nor does Jack Grealish and he has lived there all his life.

But is this fair to Jack? Is he unintelligent? Or to ask another more detailed question that gets at the same point, what really is intelligence?

When I tell people I home educate my children often their eyes widen. Well you must be intelligent to be able to do that their eyes tell me. I know this because they follow it up by verbalising that sentiment within the next couple of seconds.

But am I really? Or to bring two threads together, what is it that makes them assume that I must be intelligent, in a way that they would probably assume Jack Grealish is not?

School.

You ask a teenager preparing for their GCSE’s what it means to be intelligent and you will generally receive an answer that somewhere within contains the words “high” and “grades”. Sadly it is rare for someone who has been through mainstream education to loosen their relationship with the notion that intelligence maps to the things that school prioritises.

To most of us it is clear what school prioritises: English, Maths and Science clearly form the tip of the subject tree. However, there are things that school prioritises that are less obvious - critical pedagogy calls this the hidden curriculum; the lessons, rules and norms that are not taught but that we learn anyway. And one of those is what intelligence is - how we define it.

A definition of deschooling could be the process of reflecting on, unpicking and unlearning the hidden curriculum that was internalised from all of your years in school. For me, on my deschooling journey, breaking apart my narrow definitions of what intelligence is was a seminal moment.

When I was a teenager taking my GCSE’s my definition of intelligence would have been quite simply getting high grades in the upcoming exams. Maybe with a caveat of being able to do so without putting much effort in. At that time I also played football for the county and I remember that the stereotype of footballers being unintelligent seemed to hold true. Those of us who were in the team and expected to get good GCSE’s were a significant minority.

However I think that most people would recognise that footballers do have a special “intelligence” - though we normally call it hand-eye coordination. And at school it is one of the “intelligences” that sits outside of the normal band of analytical ways of thinking that allows you to excel at English, Maths and Science, that we accept as being worthwhile, but only in some contexts. I could claim time off lessons to go travel to Birmingham to play county football matches, but my friends who were into shooting rabbits and pheasants in the Herefordshire countryside could never have got time off to go clay pigeon shooting so they could improve their hand-eye coordination.

This is a cultural decision, which in some sense is fine: we are a culture that values this activity over this one is a statement that I can understand. Obviously as an advocate for self-directed education I believe we are limiting children’s freedom by enforcing these preferences, but signaling and enforcing are not the same. I would argue we should set free children to explore and develop their hand eye coordination in whatever way they so choose to on their own terms.

But a culture that values (and signals) that this intelligence is more important than that one is not one I can get on board with.1 And yet school not only signals but silently enforces this view. This is the hidden curriculum of school.

We are a WEIRD society. Literally. Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic.2 And we are outliers on the spectrum of all human cultures, the least representative peoples for generalising about humans, sitting right at the edge of the bell curve, yet that is not how all our children come into the world.

[Western societies] are at the far end of the spectrum in their preference for competition over cooperation; for self-promotion over humility; for analytical over holistic thinking; for individual rather than collective success; for direct rather than indirect communication; for hierarchical rather than egalitarian conceptions of status.3

When I finally got my exam results the subject that I scored the highest in was Mathematics. Mathematics has always been one of my favourite subjects and I have always loved thinking about and studying patterns. Mathematics, according to mathematician Keith Devlin, is the science of patterns.4 Devlin goes further to argue in another book, The Math Gene,5 that mathematical thinking evolved in humans alongside the capacity for language. It is inside all of us, a latent capacity for mathematics.

To me this makes sense. Seeing patterns is a natural function of the human brain intended to help you learn. Indeed when humans aren’t able to find patterns, we can experience stress, says anthropologist and cognitive scientist Dimitris Xygalatas.

So my ability to get a high GCSE in mathematics comes not from my mathematical genes, which we all have. But comes from my particular capacity to adapt to WEIRD culture, my preference for analytical ways of thinking and capacity to endure the particular ways of teaching mathematics schools employ.6

We know that those who can’t do mathematics in a school environment can do so in different contexts: child street vendors and carpenters come up with their own algorithms to solve the problems that they are faced with daily.7 Piotr Wozniak believe it is toxic memories that are causing these blockages in specific domains that do not present in other domains. We need to enjoy being with and doing the learning for it to really consolidate. We can only learn and we can only pattern seek when we are happy, and most people are happy when they are approaching something on their own terms.

Into my twenties I remained good at both football and maths. I studied engineering at University and I played football at a semi-professional level until I retired early at the age of 25. Ten years later and I have recently started playing again for a local pub team on a Sunday morning and I felt that it took a few months to shake some of the rustiness of that ten year gap off. However, one of the things that I am still adapting to is the other people in my team.

There has been a revolution in the way football is played since I last played and the game has become more tactical and player positioning around the pitch relative to your teammates more important. These changes have brought with them changes in the lexicon of the game and a term that is oft used now is patterns of play. The patterns of play are the ways in which different teams move the ball around the pitch in almost predetermined routines with players in specific formations just for specific instances.

When I say that I am adapting to other people I mean that the patterns of play that I am used to don’t occur. I do something on the pitch and look up expecting to see my teammates doing specific things in response, making certain runs, and they don’t happen. At first I found it jarring, but now I am getting used to it.

Based on the level I used to play the patterns I am expecting to see are not complicated, but at Man City there are patterns of play for almost every situation and all this has to be internalised and recalled at intense speed. It often takes new players at least a year to get to grips with this new way of playing and the level of information required to be internalised to embed itself in fully. Funnily enough after a year of not quite looking like his old self Jack Grealish has come to play more and more in recent months and is probably playing his best football since moving to Man City.

I would argue all of this is requiring of the mathematical gene. Patterns of play are literally that, patterns, and for Premier League footballers these patterns are practiced daily until they become almost intuitive and they engage with them in a highly embodied way in an extremely fast environment. All of this is performance using mathematical thinking at a high level of competence. Doesn’t sound unintelligent to me. Doesn’t sound like someone with just a gift for great hand-eye coordination.

Maybe you paused reading this earlier to watch the video of Jack running away from having to locate his home town on a map, or maybe you took my word for it. Maybe you went on to watch more of that compilation video and saw an interviewer ask him if he really did have an encyclopedic knowledge about football. In the context of the video of him being “unintelligent” we are meant to find it mildly amusing that he doesn’t know what an encyclopedia is, however, it seems interesting to me that someone who is clearly so easily labelled as “unintelligent” could be called encyclopedic at the same time. This juxtaposition is revealing.

When I was seven my father bought me a book about football. It had a list of lots of the best footballers from around Europe with stats and information and then in the back it had all the league tables from around Europe and how they had finished the previous season.

I was reading it in the car once when my dad asked to see it, flicked to the back and randomly asked me who finished fourth in the Slovenian league last year. When I instantly responded correctly his jaw visibly dropped. At that time my knowledge of football was also encyclopedic because it was my greatest passion, learning about it was easy, building up knowledge, however utterly random and trivial, was pleasurable and therefore coherent memories that were stable and easily retrievable were made because I had already built a rich semantic network of football knowledge.

Piotr Wozniak says that the ease “with which we remember is strongly related to how a piece of knowledge is connected with the rest of the body of knowledge.”8 Semantic learning is learning in which the new piece of knowledge fits in easily to our existing framework of memories, connections are rich and easily made. Mnemonic learning is when we use techniques such as memory palaces or a peg list to remember facts that have no relevance to us, for example a phone number that we break into chunks.

Asemantic learning is when learning is difficult because the knowledge is not easily connected to preexisting knowledge, or the connections are weak. At school we might call that cramming for an exam and then forgetting a few weeks later. Or, we might call it learning something that you just have no desire to learn because autonomy is important to you and therefore it doesn’t stick. We sometimes call these people the people in the bottom set.

But babies and toddlers come out naturally utilising this semantic learning, it is the only way that they can learn as it is the natural way to learn anything at that age, including about dinosaurs.

See when Jack Grealish was four and obsessed with dinosaurs as well as football his knowledge of both was encyclopedic. This is not unusual. The natural way of semantic learning leads children to find passions and go deep with them. At the age of four they have little life experience and so often they will cluster around similar topics: trucks, sports, dragons, dogs, horses, and dinosaurs. As they get older children’s interests start to broaden and as a population diversify. Herein lies the state of amazement that I see in parent’s eyes when I tell them that our children don’t attend school.

What do I do when their interests broaden and then they want to go deep with them? What about when they want to learn algebra? How do I support that?

Erik Hoel has written an interesting series on why we stopped making Einsteins. For him it is the decline of academic tutoring. And Henrik Karlson has taken up the mantle and looked at the biographies of childhoods of exceptional people and drawn similar conclusions but with the addition of the intensely rich intellectual milieu that was created around the child.

Pur simply, previously in history smart people with access to other smart people created environments where the child was raised around, wait for it, smart people. But in the early 1800’s if you were a carpenter you created an environment of carpenting, if you butchered an environment of butchering.

But we live in a new age, information is not scarce. Smart people can be bought into your social milieu through the magic of YouTube. When Charles Darwin was born in 1809 to a rich doctor and financier he had access to a good education and his grandfather Erasmus Darwin who had written a book briefly touching on topics that his grandson would go on to develop into a theory of evolution. The son of the butcher, the baker, and the candlestick maker had access to, respectively, the butcher, the baker and the candlestick maker. But now every child regardless of their parents relationships to making candles has access to the natural sciences: David Attenborough, Steve Irwin, and the MIT course Introduction to Biology - The Secret of Life are all just waiting for them on the interweb. The fact that you invariably know a four year old who knows everything there is to know about dinosaurs confirms this.

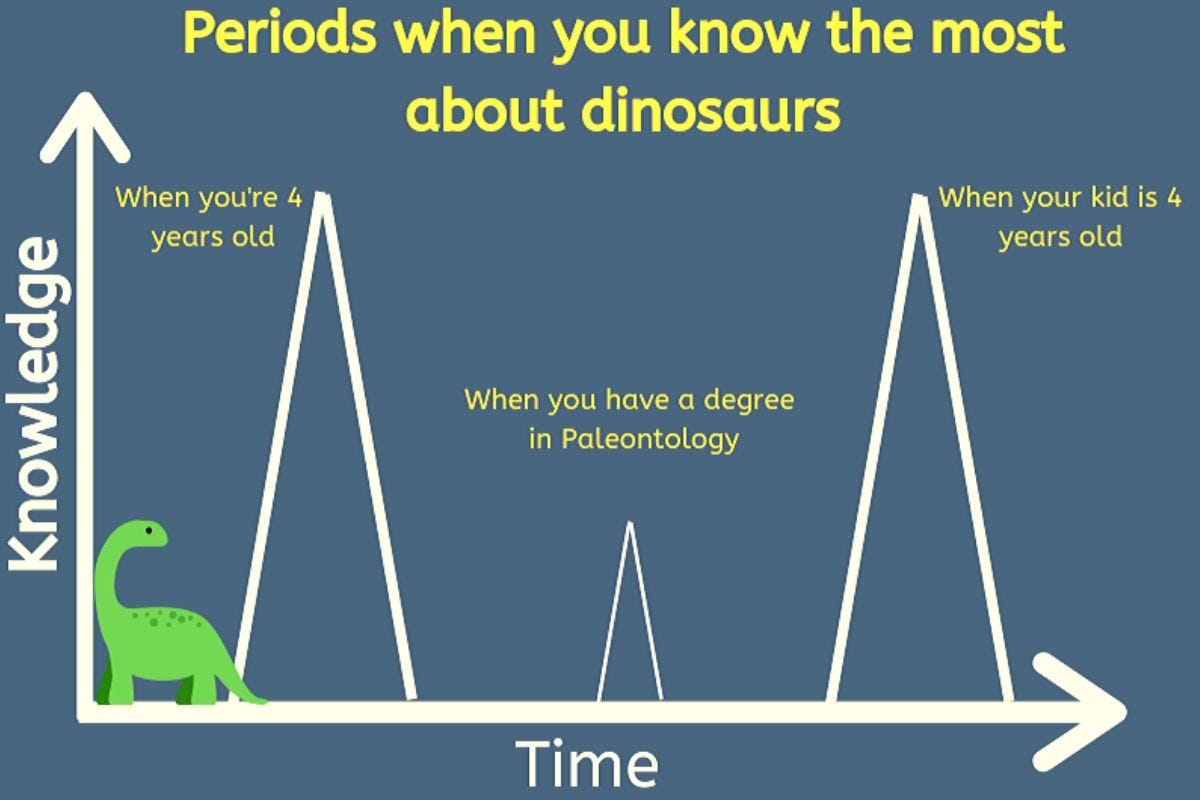

It’s time for a meme

Yes, when Jack Grealish was four not only did he know everything there was to know about Aston Villa football club, he also knew everything there was to know about dinosaurs, but here’s the kicker, so did his mum.

The brain, we now know, is plastic, meaning that learning is not confined to childhood but can continue on indefinitely into adulthood and it is how every parent who has a child who has got into dinosaurs is also an expert. It works a little like this.

Plastic brain + child’s interests = adult learning as semantic network is triggered.

But here is the revolutionary part: this formula doesn’t get turned off when your child grows out of dinosaurs and goes to school. This is a formula for life!

I teach maths to home educated and unschooled children and sometimes I give talks on this at conferences and forums. And they are the most rewarding thing I do. I get to spend an hour changing parent’s perceptions of maths, giving them permission to believe that they can like, even enjoy, maths and letting them know that they can work alongside their children to understand it again and they will enjoy it - because maths trauma is just that trauma, but it is never trauma about maths, it is always about the way it was taught.

This is not to say that if you home educate your children that they will not outgrow your knowledge base at some point before adulthood. They will. But that is fine, and what you should want, and they will be able to do so because information is not scarce anymore. Your job is not to hang in their for the ride, but to enjoy the pleasure of being taken for a ride because that is what your child’s interests will do and just by caring for them deeply you are inevitably going to pick up a lot of what they do on the way.

In conclusion

Jack Grealish show us that if you love something you can get encyclopedic despite however unintelligent you might seem. Because unintelligent, in our culture, normally just means resistant or ambivalent to a curriculum that to many demands asemantic learning.

I believe his football intelligence shows that mathematical thinking and pattern seeking intelligence can appear in different places and we would do well to recognise this in our pedagogy. Embodied mathematical thinking and learning maths through embodied activities9 run counter to the analytical approach of learning math. We need to shed this fixation on a particular way of teaching and realise that there are multiple different ways of approaching the creative subject of mathematics. As maths is a web we would do well to throw away the notion that there is a path that runs through maths from numbers to algebra to calculus and that a more holistic approach to learning maths is possible, jumping in to different parts of maths at different points, going down various mathematical rabbit holes, just like a lengthy YouTube session. Here's a thought, why not connect the two? Maybe maths and YouTube are made for each other?

And his mum, who loved learning about dinosaurs too, shows us that we are never to late to go deep on something with our kids, and if we just hold their tiny T. Rex hands through the learning process we might find that we are still learning alongside them when their voice breaks and it is our hand that now fits inside of theirs.

The distinction that is important here is that it is normal for cultures to have preferences for activities. The games we play make up our culture as much as the myths, rituals and customs. But a child born with extremely good hand eye coordination can still become fluent in this gift whether that be through football or shooting depending on the cultural situation they find themselves in. This signaling of preferential activities is only limiting in the sense that all cultures are by definition limiting.

But to say that specific intelligences are preferential to others is tantamount to saying that specific children are preferential to others. To see what that thread looks like if you pull it nice and hard all the way to its roots then I recommend reading Carol Black’s essay A Thousand Rivers, found at footnote 3.

https://www2.psych.ubc.ca/~henrich/pdfs/WeirdPeople.pdf

http://carolblack.org/a-thousand-rivers

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Mathematics-Science-Patterns-Keith-Devlin/dp/0805073442

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Math-Gene-Mathematical-Thinking-Evolved/dp/0465016197/

Natural Math is a great resource for a conceptual shift in thinking about mathematics education and pedagogy and one that emphasises the holistic over the analytical. In a sense they are de-WEIRDing mathematics. Find them here https://naturalmath.com/

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Street-Mathematics-School-Learning-Doing/dp/0521388139

https://supermemo.guru/wiki/Semantic_learning

https://blogs.ams.org/matheducation/2016/02/08/learning-mathematics-through-embodied-activities/

I took Keith Devlin's Mathematical Thinking course on Coursera and it was like a key to a whole new way of thinking about maths as sets and patterns, rather than as a random box of jumbled tools. There's always a right explanation somewhere out there for each person, but there is no single right explanation for everyone.

affirmative: maths and YouTube are made for each other?