I have been tricked into starting a blog and writing for the Soaring Twenties Social Club’s symposium, a monthly anthology where each entry from the club takes inspiration from a set theme. This month’s theme is procrastination. I’ve left some extensive footnotes on the pedagogy, theory and practice of self-directed education to keep this from becoming too long.

Where have you come from?

Where are you right now?

Where would you like to go?

What are your goals to get there?

And, most importantly, what does success look like to you?

At the start of every term at the self-directed education1 project I work at we take a group of ten to fourteen year olds and spend a week musing on these questions in preparation for fleshing out a learning agreement for the next twelve weeks: a roadmap and working document of what we want to achieve that term. Every subsequent week each small group meets for an hour and discusses the progress they have made towards their goals with the other members who give feedback and suggestions and a new weekly plan is made. These young people choose to opt into this more structured learning program modelled on self-managed learning2 when they feel ready to progress towards their goals in a more directed manner.

As well as challenging and supporting them in the role of mentor we also model going through the cycle of a learning agreement by undergoing the process ourselves, allowing them to challenge and support us as we proceed with our goals.

We ask these questions of the young people we work with to instigate a process of reflecting not just on their learning, but also their goal formation. These questions are not limited to “education” as conceived of in and by schools, these questions are framed in a context where we ask them what they value in life more broadly. One person might say: world travel and music. Another: staying close to family and music. Are these goals equally as compatible? What does a musician do for a living? What are the ways in which musicians make money? What does the pattern language of being a musician look like and do they fit with your other aims? How does the fact that your folks live in the city/in a hobbit hole in deepest, darkest Somerset affect this? Shall we bring in a musician for you to discuss this with?

These questions run alongside questions of the more practical hows of improvement and mastery that a music teacher might nudge a student towards considering.

I often describe it as an initiation into adulthood,3 but this is, in a very real sense, play. It is play, not in the frivolous colloquially understood meaning, but in the evolutionary anthropological meaning of play, what John Vervaeke would call serious play. The framework we use scaffolds the young people to develop their metacognition. But due to the self-directed nature of the project we allow them to play within the scaffolding. The means of play towards the ends of learning interacting with the means of the framework towards the ends of developing metacognition. By this I mean that, for example, we stress to parents of prospective students that the "success" of the projects they undertake at the age of eleven is in no means as important as what thoughts they are developing around managing projects in general.

Moreover, we are comfortable with someone attending who feels they do not have any goals they want to share. For the sitting with the group and listening to other people’s goals and offering feedback to them is a way to play with the framework and ultimately of immense value to that individual as they use that process to reflect on learning processes and goal formations and grow comfortable with the format enough to offer up some goals of their own later down the line.4

When I was twenty five, thirty seemed like it was probably sort of old. And then I hit thirty and I realised that I was only just on the cusp of straightening out of the first bend and heading down the back straight; suddenly the home stretch seemed much more distant.

When I was twenty five, thirty seemed like it was basically around the corner. And then I hit thirty and realised that whilst those five years had seemingly sprinted by, looking back I saw a month of Sundays after a month of Sundays.

When I was thirty, thirty five seemed like it was actually sort of old. When I was twenty five I used to claim I had reached middle age. After all my life expectancy was roughly seventy five, ergo I was now in the middle third and ergo allowed to use words like ergo instead of therefore. But I am now on the cusp of thirty five approaching something closer to an actual culturally agreed middle age and I feel even more like I am just starting my life.

When I was thirty, thirty five seemed like it was basically around the corner. It seemed people in my friendship circle were popping babies out with the ferocity and frequency that we used to pop french bangers together on the school playground. The pace of life was seemingly increasing; plotting attendances at christenings against time suddenly returns an exponential curve.

Where have you come from?

Where are you right now?

Where would you like to go?

What are your goals to get there?

And, most importantly, what does success look like to you?

We ask these questions again at the start of every term because our response to them depends very much with where we perceive ourselves to be in life at that moment. Every time we, as mentors, introduce each question we model how we would answer it on the board first and I am surprised every time by how different each answer I give is compared to the term previous.

When I was twenty five being thirty did seem old, it seemed serious, not in the serious play sort of serious, but in the mortgage, kids, marriage sort of serious. By the time I was thirty I had a three year old daughter and life had got more serious, but through the process of fatherhood I had situated myself generationally for the first time. I was not looking at time in such a ego-centric linear, but more cyclically; my perspective on time had shifted. It was around this time that I fully understood the obvious fact that my father was not perennially forty but by now in his sixties.5

But that perspectival shift cuts both ways. When I was twenty five I retired from football. I had been playing in various semi-professional leagues since I was eighteen and in the previous season had just played for the first team at Manchester University, but sadly I got kicked out and sent to Coventry, and through that process lost interest in football. Yes, I had a big project that I wanted to undertake at University that took up three years of my life and that I did ultimately succeed at. But I bullshitted myself that in footballing terms, the five years from twenty five to thirty was not that long; probably to make the decision easier. I nested that decision in a pocket of temporal understanding that ran counter to my wider perspective at the time. Looking back it was month of Sunday league matches after month of Sunday league matches I potentially turned my back on.

Then at thirty I realised that I had so much more time left for all the things that I wanted to master in my life, but also that nature abhors a vacuum and having children is one of nature’s ways of hoovering up all your time in the present. The truth is that your perspective informs your decision making. You could rebel against the realisation that having young children takes up a vast portion of your time, but you would be doing them and ultimately yourself a disservice. But maybe you can play with your perspective, tweak it at the margins so to speak and make just enough space for yourself in the process.

I would guess the most common shared experience of procrastination today is the University deadline. Almost everyone who goes to University will experience writing an essay on deadline day and frantically trying to upload it with five minutes to go, cursing themselves for not heeding the folk wisdom that a watched Turnitin submission never uploads. Having had the assignment for weeks they procrastinate until what seems like the very last minute; until the margins of time can’t be tweaked any longer, and then they crack on and do it, or not… (bye Manchester, hello Coventry).

Here the extrinsic motivation of getting the grade and the imposition of the assignment placed on the student by the teacher cannot foster enough intrinsic motivation for them to get on and do it until the only variable left, time, catches up with them.

At the self-directed education community where I work all the young people create and undertake their own projects. Some kids have never been to school and have been unschooled6 their whole lives, whilst others have recently left school due to traumatic experiences and are in the process of deschooling7 themselves, learning to listen to and trust their intrinsic motivations again.

One of the things that I often ponder is where the overlap between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation intersect. In a setting such as ours where almost all young people are left to start reading when they feel ready to, is the desire to read due to a perceived sense of shame8 an external factor or an internal drive to master autonomy?

Are projects that are undertaken collaboratively motivated solely intrinsically, or how much pressure from their peers is driving them as a motivating factor? I do not think that a simple dualistic notion of inside of me, outside of me, exists in the real world of social human beings in community. In a world so bereft of intrinsic motivation, or rather so saturated with people externally motivated in the workplace this demarcation is maybe largely academic but in our setting I find it a valuable reflective practice. Part of our job as facilitators is to realise how much each particular young person can be pushed and guided, how much external motivation they will respond to at that time with that task, and notice when we need to throttle back so as not to lose them.

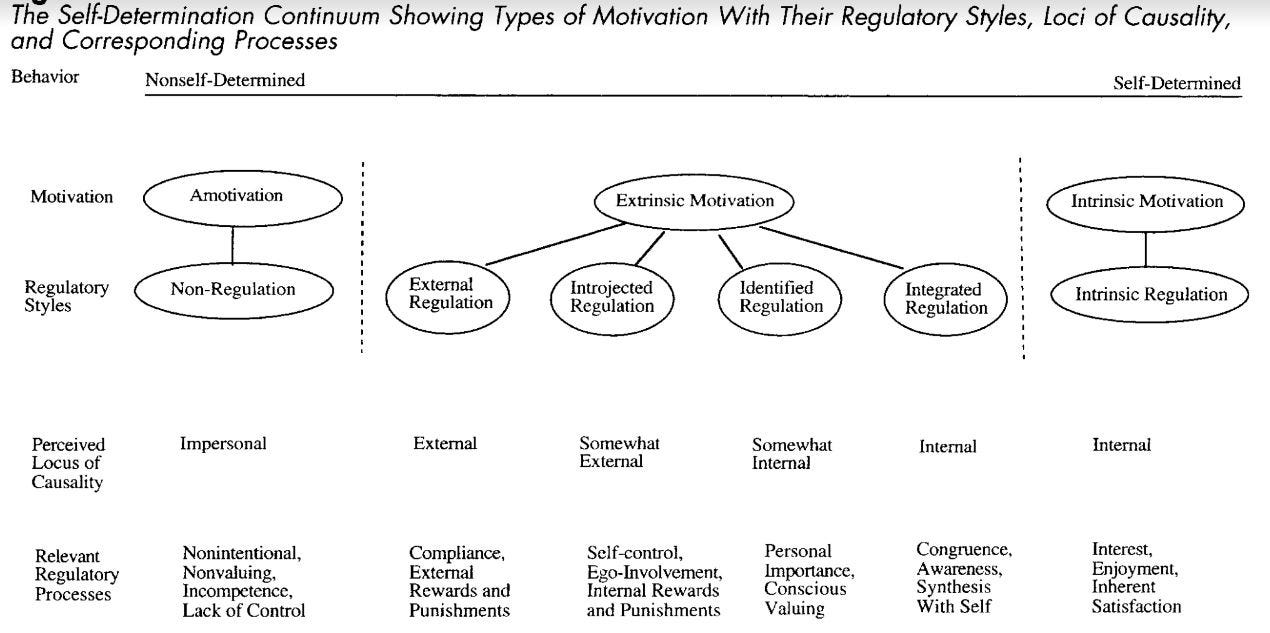

Richard Ryan and Edward Deci’s self-determination theory posits an answer to this reflection.9 They think the dichotomy is overstated and reified and have a theory that posits that external motivations can be perceived by the self to differing degrees reflecting the value to which internalisation (the taking in of an external motivation) or integration (taking into the self so that it will in future emanate from within) occurs. Self-determination theory posits that there are three innate psychological needs - competence, autonomy, and relatedness - which when in place enhance motivation. It is relatedness, the increased connections you feel within your social milieu, that dictates how integrated, or not, external motivations become. They identify four potential responses to external motivation.

External regulation: the response to rewards or punishments.

Introjected regulation: internal prods or pressures to behave because you think you should do. This is often internal to person but not to the self.

Identified regulation: adopted not because they feel they should but feel it’s personally important.

Integrated regulation: this is the assimilation of separate identifications into one’s coherent sense of self. Here environmental pressures are not perceived as external, coercive forces, but relevant information. A loving parent’s instruction to help to tidy up are not seen as controlling but something to be listened to as valid information worthy of attention and responding to.

Three factors affect whether a person may integrate an external pressure. Meaningful rationale so personal importance is seen, acknowledgment of feelings (or what Adam Mastroianni might from another perspective call the vibes10) and interpersonal ambience that emphasises choice rather than control. This ambience is the skill of the facilitator. How do we create the right interpersonal ambience, or tune into it when it is already there?

Where have you come from?

Where are you right now?

Where would you like to go?

What are your goals to get there?

And, most importantly, what does success look like to you?

Of these five questions the last two are the most important ones. And our role as mentors is to play with the young people and deepen their perspectival understanding of time. We can’t expect them to have all the answers and map perfect projects out, it is bound to be messy. But messiness and play are bedfellows. Child’s play is the making of the adult human; it is the important “work” of the child. The last two questions ask these teenagers to play with tweaking the margins of time so to speak, because they are playing that game to tend towards the mastery of ultimately getting a more profound grip on their perspectival understanding of time in regards to their own goals. With extrinsic motivation time (or the sudden lack of it) is the driver, but when you are working in the realm of intrinsically motivated projects time is the variable we now control and need to learn to play with. What does success look like for me? doesn’t have to have a timestamp attached to it but often will be a more useful waypoint if it does.

I want to note at this stage that I am not saying that intrinsically motivated people do not procrastinate. We often see a lot of procrastination. We have created a goal matrix to alert us to when a student creates tasks related to a specific goal for a number of weeks in a row and does not make any effort to undertake them. Time is the variable that they need to learn to control because to procrastinate is human. But procrastination is often a habit and so understanding how they can control that is a large part of the programme. At the age of twelve knowing whether you want a goal that you think you want is also quite a challenge. Often the procrastination is telling us about our intrinsic motivations; do we actually want to achieve this goal as much as we previously thought. If we decide that we do then we have to work out how to make the variable of time work for us. Procrastination can be an indicator that we were off with our initial goal formation, which as a teenager exploring your potential interests is a valuable learning experience, however, it can also be indicative that you need assistance in thinking about how to progress towards goals that you are actually passionate about.

“Be more specific!”

Me every week to at least one person in my learning circle.

As part of our framework we have a form that prompts considerations on your upcoming weekly plan. Firstly, each goal can be broken down into it’s constituent tasks for the week. But the young people find it hard to get specific about tasks, to realise when they can be broken down further into smaller discrete parts.

Each specific task can be planned with respect to time: when, where and how often that week you will undertake that task. Again young people at first find it hard to be specific here also. This prompt is always undertaken in relation to each specific sub-task. To assist them we try to spend one session with each student mapping out a complete breakdown of one of their goals into as many constituent tasks as possible so they get used to moving from the gestalt of the goal to the concrete of the individual tasks and situating it all temporally.

This is where the most challenge, but the most fruit lies. Those not opting into the self-managed learning project at the learning community undertake their own projects using agile learning tools.11 The main difference in the two approaches is that one starts with their immediate needs and wants and works outwards, whilst the other starts with longer term goals and then investigates how they can be made to bear, from out to in, but then back out (and then in, ad infinitum) again through continuous reflection.

The above two prompts, week after week simultaneously stretch out and contract time in the minds of our young people as they move between the large goal of owning a café and the shorter term action of handing in a job application for the local café as a potwasher. Whilst also compressing the seemingly endless time of a self-directed teenagers week as they seek out the moments in which to set aside for focus. In essence they practise the practice of starting the essay on time. But they also practise moving towards the self-directed goal of getting a degree, because let’s be honest we have let a white lie slip us by earlier. The student that procrastinated above is not in school, they are in University; they are there by choice. They have stated they have an intrinsic motivation to study mechanical engineering for whatever reason. So why can they not bring that motivation to bear and do that final piece of coursework?

“I already had a wealth of experience with self-directed study. I knew how to motivate myself, manage my time, and complete assignments without the structure that most traditional students are accustomed to. … I know how to figure things out for myself and how to get help when I need it.”

I believe that having been self-directing their education for many years these learners have a much better grip on the nexus of time and intrinsic motivation that they get how to perceive and allocate time in a way that allows them to get it done promptly (let us not kid ourselves that they are so intrinsically motivated they do it the day it is set). This is a practice and a habit and the formation thereof is the bedrock upon which our program is built. Take this process of practicing the same piece of music for six months in preparation for an audition at Juilliard and it sums up playing with the variable of time12 as you work towards your goals and how that process is actually about more than just the goal itself; but creating a deepening of your perspectival understanding of time as it relates to your needs and wants.

When he told his teacher, Amy Barston, he was bored, she told him boredom in practice comes from a lack of engagement. She showed him how to recognise disengagement. Then she taught him to look more closely at each note and listen more deeply with his ears and his heart.

He learned to practice by changing the rhythm of the piece. He learned to play one note at a time with a tuner. He learned to play each measure with a different metronome timing, and then he played the piece so slowly it took 20 minutes instead of just four.

During these insane lessons where Amy and my son spent one hour on five notes, the more we worked on the art of practicing the more I saw that practice is a method to do anything ambitious and difficult. He learned to create a system and process instead of just focusing on the goal itself.

In September I said that I was going to start playing football again. This wasn’t the first time. Over the years I have attempted various times to “get fit”; sometimes attaching that aim to playing football again. I said I was going to do it in September in my learning circle. I don’t think I did a thing towards it. In January I said again I was going to get fit in my learning circle. My training regime was more Rafael Nada Thing than Rafael Nadal. In April came the same opportunity to state the goal so I pulled the trigger. To be fair this time I did go running, maybe a couple miles a pop, every four or five days. I had been here before though and my usual modus operandi was to just let it peter out, mostly because going from nothing to a couple of miles meant it took me five days to recover and that limited my capacity for habit creation. Then a month ago I ran 5k on Sunday, 5k on Tuesday, 5k on Thursday and have been keeping it up ever since. This aim that I have had for seven eight years on and off, that I had been biannually attempting yet procrastinating with every time it came round again, I was finally making some solid progress towards. How come? Community.

The reason we meet weekly in small learning circles is because community is central to human beings. I believe it is in community that the nexus of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation intersect. Pursuing your own projects builds the practice of tuning into your intrinsic motivations and noticing your needs and wants. Using a reflective process allows you to get a more optimal grip on how to manage them through time and therefore increase your chances of continually meeting your needs and wants. But doing so in community gives you the opportunity to input other people’s perspectives and offers you accountability. We will only internalise external expectations if they come from sources that we value and/or trust.

Unschoolers are left to read under their own direction but the external expectation of having books around the house, watching parents reading everyday, or having your grandparents say I want to read you this book, why don’t you read this page to me actually, I can’t read you the menu just yet as I am busy; these all exist outside the person, but they will be internalised as a drive to read if they are infrequent enough not to come across as an imposition13 and offered in love. In unschooling practice relationships are key to learning taking place. The child is trusted what to learn but also who/where to learn from. You can’t have the first without the second, learning must occur from some source and it is as much (if not more) the source that is sought out rather than the information. Trust is the conduit through which the information flows towards the child, and trust is rooted in love. But trust also requires a community; you can’t trust in isolation.

The weekly learning circle meeting is the where the nexus of time and intrinsic motivation, and intrinsic motivation and external motivation meet.

The individual process of goal formation and reflection, allows you to create your projects (listen to your internal motivations fully), the reflective process allows you to get an optimal grip on time as it relates to your projects (the perspectival understanding of how much time do I want to offer this project in relation to other projects), the feedback other’s give you gives you another perspective on your own plans (you internalise different perspectives on your project, some of which are related to getting an optimal grip on your perspectival knowing of time), listening to other people’s goals and reflections gives you another perspective (you see how they shift through and sort time to work on their own plans), and finally by going through this process in a small group weekly you build trust thereby increasing the likelihood of the internalisation of other’s opinions (external motivations internalised as intrinsic motivations). This is the culture creation of a self-directed education space for young people.

This is meant to be an essay on procrastination. I think we are finally ready to tie it all together. I know it seems like I have been putting it off.

There is no single definable reason why I ran three 5k’s that week, but whilst I may have sketched out the rough method and gathered most of the ingredients in this essay there is one key ingredient that we still need to get out the proverbial brain cupboard. In January I joined the Soaring Twenties Social Club (STSC), a discord channel for artists who want to move beyond “content” creation and towards the creation of art. The channel contains over 200 people from around the globe: painters, comedians, photographers, podcasters, and writers of fiction, non-fiction, poetry, essays, and more. I didn’t have a particular interest in any creative endeavour that I wanted to cultivate, but I really enjoyed the founder Tom’s essays and wanted to support the project.

There are three things I want to briefly say about this project. Firstly, they now publish a weekly anthology of everyone’s work from the club with consistently high productivity and quality. As one user noted people join the club and just see lot’s of people just making art and are either intimidated and leave or inspired and just start creating too. In the language of self-directed education they are listening to their intrinsic motivation and engaging in deep and serious play.14

Secondly, they have created a space where there is a real drive to help other people develop their craft with channels for feedback on works in progress that are constantly buzzing with constructive criticism, and other channels where the craft of creating art can be discussed in general.

And thirdly, they have a few off topic channels including an exercise channel where a reasonable percentage of members post their daily workout regime.

The Soaring Twenties Social Club discord channel is an interesting intellectual space for me as a facilitator at a self-directed education community. Tom has created a space where people are joining and then just making art and doing so as a collective and a community. This is the culture creation of a self-directed education space for artists.

That Sunday afternoon I went for that first 5k run I had been in the park with my children in the morning. Seeing a football team clearly doing their pre-season training, on a whim I decided to wander over and ask if I could sign up and they invited me back next weekend. Going home I realised I now had a community of people that I was accountable to and internalising that external pressure I decided I had to get as fit as possible before next weekend. The community of people were made more powerful a driver due to it being a whim and I had no idea what the team was even called, how good they were, and how embarrassing it might be for me to turn up next week without putting in the work. So I ran, and ran, and ran. But what had spurred that whim?

Certainly being involved in coaching my daughters first year of football herself had rekindled some of my internal motivation to play football, reminding me of the joys of team sports. Being involved in a learning community where play is so highly valued as a means and an end and serious play so valourised reminded me that playing football was not only an important part of my identity but actually a part of my identity where play was its most fervent. Being part of a learning circle committed to reflective practices weekly helped me train the process of getting an optimal grip on time. Combining that with my understanding of the importance of play in life and football as play made me reevaluate my priorities; I tweaked the margins of time to see I could (and in fact very much should)15 find time in my life for a game every Sunday without impinging on the relationships with my family. Finally being part of the STSC allowed me to witness a community of adults involved in deep play as a collective16 and seeing the people in the exercise channel continually turning up day after day allowed me to get a more optimal grip on time as I thought about the work required to get fit enough to play football.

I think we sometimes forget that a “big inspirational moment”, possibly because of our cultural obsession with grandiosity, is a poor substitute for quiet, consistent reminders. Previously I might have turned to seemingly powerfully inspirational Goggins or Jocko videos to try to help leverage a sudden burst of intrinsic motivation for undertaking an exercise practice, but the daily posting of a Slav telling you they have done some pull ups or an Aussie benching yet again at 0400 hours is so much more powerful at getting you stretch and compress your perspective of time as you consider creating habits around exercise.

I started this essay saying I got tricked into starting and writing a blog. See this was originally just a post that I was going to drop into the discord channel to say: I have started football training and I think that this channel has a had a good influence on me doing so, so thanks. Mainly to say that maybe not all the inspiring work you do might influence people into creating art that you can then witness but that this channel can still have a positive effects in people’s lives in other ways. Anyway, the comment got sort of long. Almost blog long length. The knowledge that actually you can just start a blog to say something was deeply embedded in my brain from six months of watching STSC member after member do so , and the themes I was touching on were sort of related to procrastination and that was the monthly symposium topic. So I thought maybe I could start a blog just to say how I haven’t started a blog yet. And so I did. Just to say thanks for the inspiration.17

Thanks for the inspiration.

Self-directed education is education that derives from the self-chosen activities and life experiences of the learner, whether or not those activities were chosen deliberately for the purpose of education.

Self-managed learning was developed by Professor Ian Cunningham who runs the Self-Managed Learning College in Brighton, UK.

By this I mean in the broader sense that the freeform nature and spontaneity of play that has pervaded their previous experiences with us must start to be curtailed. Signing up to the self-directed programme requires making a contract to agree to not only share your needs, wants and goals, but to listen to others and give them feedback. It requires much more attention and seriousness than is required in other meetings at the learning community (which is hard work) and is much less ego-centric as the young people learn to give (are sort of required to give) themselves and their opinions to the community. Within the consent-based sociocratic approach we take young people are very much involved in culture creation from their very first day with us, however, by joining this programme they expand this input to the creation of other people’s projects and goals (in a more directed, specific and consistent way) and therefore start to create a much more intentional community.

As I am sure you understand in our culture for someone who is just starting their teenage years they still have the freedom to play, and they still have enough time on their side to play at the pace that they want to. Also, often young people come to our project straight out of a school experience that has left them traumatised to anything that resembles “structured learning” and they need to time to see what we are doing as different.

Previously I had intellectually understood that he had an age and when asked what that was I could bring that answer to my mind in a few seconds but at a deeper level it seemed that I felt that he was still around forty. I think maybe that that was a reflection of more ego-centrism and possibly tied into the age that he was when I became officially an adult, the stuck liminal space that I saw in him was a reflection of the liminal space between official adulthood and actually feeling like I embodied some of the actuality of adulthood.

Unschooling is a educational philosophy where there is no set curriculum at all, and the learning is driven primarily by each individual child’s interests.

Deschooling refers to the process at which a young person who has been to school and then left takes to unpick the patterns of school. In the context of this essay what that means is learning to trust their intrinsic motivations to drive the learning (the process of becoming an effective unschooler). Among the unschooling community there is a widely known formula that for every year a child has been in school they will need a month of just free play before any external motivations will be paid any serious heed. Or as stated in the next paragraph of the essay, this time is the rough requirement before external pressures that operate at the nexus of internal-external motivations will be viewed internally and not outright rejected.

The shame in this case is perceived as within the project no one shames anyone for their lack of reading comprehension but when this shame is expressed by someone it is obvious something has birthed it; wider societal expectations and family culture obviously also have large influences on our young people. They could leave their shame at the door, but it’s hard for a eight year old to have that wider perspective on things. Furthermore, would they want to? As the shame is driving the learning process as they take steps to start a daily practice of reading with a mentor.

Most of the rest of this section relies on various papers by these two: Beyond the Intrinsic-Extrinsic Dichotomy (1992); Self-Determination Theory and the facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development and Well-Being (2000); and Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behaviour (2000).

See here and I don’t know how to get rid of that whopping great link so I am just going to leave it like that.

Agile learning tools are common in software companies and are borrowed and exapted for self-directed education by Agile Learning Centers, of which we are one. We employ a gardening analogy and move projects around a communal whiteboard. Anyone can plant a project, which will start as a seedling (an idea), turn into a sproutling (when it is brought to the wider community’s attention by the initiator), start growing (when the project is in process), and sprout and bud when they are completed. We also compost ideas that are in either a state of a long pause or have been shelved, party to track them, but also because out of the rich, black humus of previous ideas can sprout new plans that carry their essence forward.

This is a rather extreme example, but sometimes those from the extremities highlight the point best. The article also goes on to make the point I do about the necessity of realising what is the smallest sub-task that each goal can be broken down into.

Unschooled children all have this face that they pull when they sense you are trying to “teach them” something that they have not solicited: a mildly annoyed, slightly frustrated why, with a quizzical eyebrow raise saying stop please. If you are not used to it and pursue unbeknownst you run the risk of being told to fuck off.

Yes, art of all types is obviously an example of deep and serious play.

Unschooling children need role models to demonstrate what being an adult looks like. Adults therefore need to take time out for themselves to tend to their needs, but also to take time out for themselves just to play. Unschooling philosophy says that play is the essence of learning, and by default should be the essence of learning throughout life. The project fails if the child can’t see that that is a truth embodied by the adults in their lives. That creates a cognitive dissonance.

I think there is something important in the distinction between trying to embody a relationship of equals in a community as an adult working with teenagers and actually being in a community of adults who are equals. Also, the difficulties that adults have with deep play is symptomatic of a deep malaise in our culture. I often find that parents who unschool their children often even have difficult relationships to play themselves. We went camping once with a group of unschooling families and a parent commented on the fact that after taking the tent out the boot of the car I noticed I now had a football and an empty boot to play with and was repeatedly attempting to kick the ball into the boot from about thirty yards. I don’t remember what they said but it was along the lines of I wouldn’t have thought to play before putting up my tent.

I started writing this essay the weekend before the last week of term. At the end of year reflection circle I shared a similar thanks to the young people for their input into my life over the previous year that had spurred me on to seeing play in a different light and helped me move towards joining a football team.

Just spent an hour writing a response to this but a glitch has deleted it. A huge thank you is a poor substitute but thank you.