Home

This essay is a contribution to the fourth Soaring Twenties Social Club Symposium, a monthly collaboration from STSC's writers around a set theme. Our topic in August 2022 is Home.

This post is too long for your email so to read it in full please click on the title above.

Two letters dropped through the door today. One an invitation home to suckle on the bosom of identity. The other a reminder of the ongoing work the wandering nomad has of tying the threads running between their past, present and future selves together into as neat a ball as possible.

I slide open the first letter and thumb through the form it is asking me to fill in. I start with name and date of birth, the usual suspects. Turning to the second page the optional tick boxes reveal themselves: age, gender and ethnicity. I don’t massively mind completing these, I am who I am after all. So I tick the bracket encompassing mid thirties, male and White (Other). I’ve not always been othered. I was born in the West Country, grew up in the Shires, my parent’s met at school in Kent, at most half a petrol tank away from where they were both born.1 But for the last year I have been refusing the simple tick of the White British and opting for the Other with it’s tantalising promise of more information to be offered on the dotted line. And I write in block capitals. HEREFORDIAN.

The contents of the second envelope is blunt with its rejections of my lies. The doctor’s surgery might let me get away with this shit, but the state knows. The household polling card has only two names on it, one of them is mine, and both are apparently BRITISH. But the state doesn’t really know. Or rather a bureaucracy can never really be sure of it’s own knowledge. Is this information correct, they ask. It is not, but they don’t care for the truth anyway. I have tried multiple times to update my partner’s nationality to no avail. The hostile environment seems not to care for the answers that it claims it wants, answers which I believe are illegal for me not to give.

I toss it straight in the bin anyway. She doesn’t need this reminder that she is not home, has never had a home, and may never have a home thrust into her face when she returns from work, places her keys on the windowsill behind the sink and gazes into the chaos of our garden filled with trampolines, footballs, balance bikes, screams and children’s pants that seemed too uncomfortable in this heatwave at multiple times today, including it seems right now.

She doesn’t need to stare through the double-glazing and be forced to choose which of the threads to tug on to get away from that moment, the future, dreaming towards the house she might one day own outright, a place to potentially spread out and down with roots, or the past, staring not out of this rented city semi, but through the small window of Katarina’s wooden cottage, taken back to an autumn morning with Alpine mist hugging tall broad pine trees on the far side of the hills and the smell of browning butter slowly simmering in a pan on the range.

The cold is coming, rolling down the Alps and over the hills. The rains have held off for almost a month now which means that they won’t come again till the spring when they will wash the snow away that is only days away from falling, choking out the mist and gripping those same trees in a much tighter, colder embrace. They’ve not long been inside, the slightly oversized slippers not designed for a child quite so small have warmed the toes but are yet to work their magic on the heels, but the fresh mug of cocoa the old woman placed in front of her might help, spreading its heat downwards to meet at the ankles. She stares out the window her mind pinballing carelessly around ideas of the upcoming snow, something she read about Eskimos and words for snow…. building snowmen with her brothers… the lightness of snow on your tongue as it falls… the faint smell of mushrooms… how snow is dense like dark rye bread… the joys of tobogganing on its thick crust over the crest of the hill behind her house and then faintly the sound of Katarina’s voice which, like the pines, she is sure has been in the background all along.

A jar waves itself in front of the window and pulls her back into the moment. Dried nettles inside. Probably the ones she wild harvested with Katarina in the spring. Another jar in the other hand; dried sage. The smell of mushrooms now toasting in the butter reminds her that lunch is soon coming. Katarina asks again, as patiently as when she showed which mushrooms from the forest they should take and which they should leave. Nettles? Sage? Maybe those chives up on the shelf. Offers of jar after jar are followed by ja after ja as the flavours of an omelette from the forest come together in the pan.

I don’t know why I started filling out forms as a Herefordian. In part because it makes me laugh inside. But for the past few years I have felt increasingly angry at the reductionism of a tick box answer to many of these questions. Why does my partner have to tick White Other but our children technically qualify for White British. Yes, they are born in this country, but if I’m sitting down at the table filling out a form for them with the plantains frying and the jollof rice steaming, or the smell of Dutch meatballs, made only the way they should be made by the way with 50-50 pork to beef, simmering away in half a kilo of butter, the potatoes boiled and waiting to be mashed and liberated from their floury clagginess with another quarter a kilo of butter, how can I reduce the story of their ancestry to a tick box? Especially one that says they are not other, they are not bigger than British, just as I am actually smaller than British, I am Herefordian first and British second.

Yet the truth of the matter is I am not even Herefordian, not really. I was born in Somerset, but in 1995 I moved to Ledbury, just seven years old. I consider myself an honourable Herefordian but know that deep down I don’t have the pedigree of some of the locals. I am not Stevie Ledbury or Luke Ledbury that is for sure. But I understand and love the place, celebrate the community of people that I grew up with, who in turn celebrate me in return, and most importantly I consider it my home.

A few years ago my best mate got married and plenty of ciders in I asked him what his plans were. She was from Cheltenham and they had been living with his parents for a few months but wanted to buy a house. Where are you going to buy I asked him. Ledbury, obviously was his response. To him it seemed incredulous that he would live anywhere else. But furthermore his caveat was outstanding.

She is happy to move from Cheltenham but I just don’t think she gets it, Ledbury is just a completely different place and I am not sure if she understands it yet.

I actually told this story just the other day to some people who were talking about their experiences of having partners from different countries and different cultures. And everyone found it hilarious. I think juxtaposed against a story about an English man marrying a Caribbean woman it seems parochial, small-minded, closeted to the idea that there are potential differences in the world that are so much greater that your differences are not worth bothering about. But I don’t believe that; there is something admirable about his worldview. Having grown up in Ledbury I also know it is different to Cheltenham in a myriad ways, and Herefordshire itself feels like a culture unto itself, and being aware of that, of what your town has to offer, what makes it unique, what it’s foibles are too, is to be fully aware of your community, your place in the world and ultimately your self; is that not to know what home is? Maybe. Though I do know that it is just as narrow minded to think that someone needs think bigger than the place that their ancestors have lived since before it was necessary to think about recording that shit on a computer database somewhere.

So is that what home is? But more importantly on a blog about self-directed education, if that is home, how does home relate to education. My friend above whose wedding I was at was my partner in crime at 17 when we got expelled from my local school and I was asked to do my final year of studies at another college. I went from messing around but on track for a good haul of A’s and B’s to not giving a toss and leaving college with a couple of D’s. Or in the eyes of a University admissions tutor, chump change.

So I hung around Ledbury. Getting expelled made me a Herefordian.

Without that I probably would have got my qualifications and moseyed off to some University acceptable enough for my parent's to discuss at dinner parties, graduated onto the treadmill of indeed, be sat in meetings competitively spouting about synergy, and every now and then when some other rootless liberal asked where I grew up tell them over a £7 pint that No, I grew up where they make cider and farm big cows, not that depressing commuter belt around London. Can you not hear my farmer twang? But who knows, in that parallel university2, I might, like my brother and sister who left the pastured cows behind for the greener grass of higher education as soon as possible, not have that farmer twang.

I did eventually go to University3 but not until my mid-twenties and those five or six years embedded me in the community in ways that were deeply rewarding. I laid down roots that I will never forget, forged friendships that will always be there waiting and reflected on politics in the context of class, home, community and scale that have influenced me immensely going forward. I am a man of the shires no doubt.

In 1995, the year I moved to Ledbury, my partner moved to Austria. She was three, born in the Netherlands, moved to Switzerland at 16 days old, lived in a hotel for six months before her parents attended Bible College in America living in Mississippi and Oklahoma during that time. Her parents are both half Dutch, her dad half English and her mum half Ghanaian. She speaks English, Dutch and German, and she has moved around thirty times in her life; the home we have lived in now for the last five years being the longest she has stayed in the same place.

Katarina was her babysitter, an old woman who lived high in the woods in a cottage nestled in a clearing, a painting waiting to happen. The church her parents founded was in a small town near the Czech border in the hills that rolled and buckled as the mountains of the Alps slowly sloped down towards the plains of the Danube. Farmers, woodsmen, hunters, timber frame builders, people who wanted to open their hearts to God and give their hands a weekly rest made up the congregation. In a way it was Herefordshire on steroids: more idyllic, more peaceful, more settled in the traditional patterns and culture that had made this corner of Austria what it was for generations.

The house that they stayed the longest in whilst living in Austria had no fences, dozens of fruit trees dotted amongst a lawn that stretched back towards the woods where the grass just faded into thick pines, a permeable boundary that the children crossed every day to play in acres of cool, dark, damp wood, and on times was crossed in the other direction by deer to birth under the cherry trees. This was the childhood that Jay Griffiths talks of in Kith. Here there was no riddle to the childscape, it was utter freedom, or at least the freedom to go as far and no further than the large river two or three miles away. Wild animals, summers spent on farms, natural swimming ponds, horse riding so ubiquitous it was basically free to ride, and ride you could, through Alpine meadows at a canter.

But in as far as the natural world offered a freedom that seems almost overly romantic, Austria was not a perfect place, far from it. At school her dyslexia went undiagnosed, instead at one school she was told that her struggles were due to her mother’s Ghanaian heritage and she was forced to do extra work after school to counter this. This claim was evidenced by a textbook that the headteacher presented to her. Let me date this more clearly for you. Whilst you were sipping champagne fretting over whether your date would kiss you at midnight and if the millennium bug would ruin the global economy, she was worrying about going back to school and sitting detention for simply being.

We’ve pulled on two of the main threads now that have led our family to homeschooling our children. My experience of being expelled and her experience of racism in the school system (which continued in the UK after they moved here to get away from the Austrian system) are the two big factors of many for why our children don’t go to school. As it is called “home”schooling, is there not elements of home woven through it deeply? The most obvious being that the education happens not in school, but at home, surely? But does it?

Unschoolers like ourselves believe that learning is happening all the time, whether you are at home, the supermarket, the park, or on a bus. But the majority of the time is spent at home, surely? Well, not necessarily. Apart from going to a learning community for fifteen hours a week we also go out to parks, to milk goats, to meet up with friends, visit libraries and museums, and much more. In fact when my daughter was only three and we were technically not homeschooling yet I would often say I was a not-stay-at-home dad as we seemed to spend nearly all our time out of the house.

I said house then, not home. I’ve used them interchangeably in that last paragraph, but are they? Or are they two contemporary synonyms who have, however, different semiological foundations?

Interestingly the question of “home”, often intertwined with the bigger idea of “community”, has been a topic that I have spent numerous hours discussing with our homeschooling friends. Modern society has provided us with a wealth of material improvements, however, it appears that along the way one of the greatest costs has been the loss of community - there is no such thing as society has become a self-fulfilling prophecy. And I think people are rightly questioning that. At least they are in the circles that I run in, and coming up with alternatives to living in urban suburbia of one of the largest cities in the UK. Maybe the answer is intentional communities? Moving onto an orchard owned by my best friend from University? Buying a large country house and sharing it with three families? We could all agree that we will move to the same quaint rural village and then we will have the benefits of the rural community and of our own? But none of these dreams materialise.4

We all have pipe dreams. I get that. And there is nothing wrong with wishful thinking every now and then. I sometimes dream of homesteading a small ranch in the foot of the Rockies, I dream about the morning view with coffee, the horse nuzzling me over the fence. The walk at dawn with the dogs that will do nothing less than recharge you every single morning. Obviously I don’t think about mucking that horse out or any of the other back breaking work and I normally only ponder it for around five minutes or so when I see someone else on the internet who lives in a beautifully wild part of the world themselves.

This is the kind of thing I casually dream about. Photo by Deanna Lewis on Unsplash

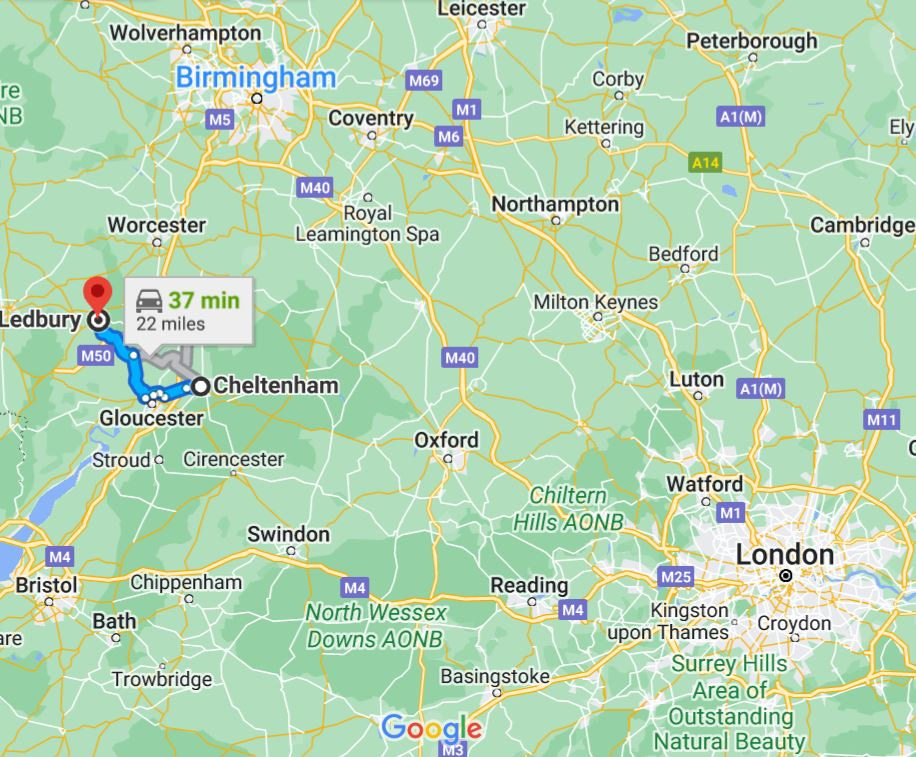

Sometimes people’s pipe dreams are more realistic. My partner wants us to buy a house soon, wants to move and dreams of what that life might look for us. But that dream is hard to nail down as evidenced by the number of houses she sends me from all around the country, saying why don’t we move here? Or here? Or here? The map below, whilst demonstrating the scatter gun approach to where we could live, does not do it justice as inevitably I have probably forgotten some places - since capturing this image I have remembered Scotland to the north and Cornwall to the south. And it does little to show that within Bristol, the city we currently live in, there is an equally broad shotgun approach to house hunting.

We could live here? And by that I mean anywhere.

But in this lies the potential for answering our question of the distinction between house and home. See the reason that she can take such an approach is that as homeschoolers we are to some degree isolated from the worst aspects of the housing market: the link between house prices and good schools. And in this freedom we can think about living anywhere in Bristol. It is probably a good idea in our position to think like that, maybe not so much applying that across the whole island however.

This is the freedom that the options above also staked their claim upon. We can move house wherever we want as we are not beholden to good schools in the same way everyone else is. And yet, they still don’t move? Maybe it is unfair. They are caught in a bind. The big dreams of their ideas are just too hard to facilitate. Modernity offers everything on a plate, but no menu as guidance. Contemplating the dreams of making a home is so much more than flicking left or right on a housing app. But then maybe they need smaller dreams?

It is also not true that homeschoolers don’t move. They very much do. It seems my friends might be the outliers. Because they are not beholden to the link between schools and houses, because they might be likely to work in more flexible careers, or both choose part-time work to help cover the childcare between them, maybe because they are freed not only from school but work being Virtuals rather than Physicals, and there are probably a plethora of other reasons, within the homeschool community it is well known that people move away reasonably often. But furthermore, even before they move away one of the great criticisms of the homeschool community, from within, is the flakiness of it. The learning community I work at exists because it fulfills a deep need, that of providing community for young people that is consistent. Hence why we ask that people sign up for the whole three days a week and not just pick and choose when to come. Community requires consistency.

Sure people still come and leave before a year is out, sometimes we have young people who need to come from school and heal their trauma for a while before carrying on their journey with the schooling system, sometimes people move away for the same reasons as above, sometimes people decide actually their child would be better facilitated not in community but at home for philosophical reasons. There is a strong sense of community within the learning community but it is a community that is constantly shifting and evolving in a way that schools, being much, much larger, are more often not.

In a previous post I spoke about self-determination theory and the three innate desires for competence, autonomy, and relatedness. I think most people homeschool because they recognise that schools do not provide young people with enough autonomy, but also because the authoritarian nature of school affects relatedness. They wish to have relationships with their children based on collaboration and co-existence rather than control, coercion and childism. And whilst I share those desires and note they have influenced my philosophy of unschooling, I note that in the floundering around of “home” and “community” we recognise that relatedness has to be something bigger than just the few people who live together in the home or in our small self-chosen community; we must relate to the wider community as well - we must share and participate in the stories of those who we commune with; society at large. I think in this lies part of our answer to the question above. House is that place, that space in which you reside, but home is bigger than that. Home seems more like how something fits together into a wider space, how the house fits into the landscape, how the people who reside inside fit into the community as well.

John Vervaeke in his Awakening from the Meaning Crisis Youtube Series talks about the post-Alexander Hellenistic period as being one of domicide - the destruction of home. In part this was physical domicide as war and empire cause destruction to people’s homes, but also a great uprooting as people moved around empire and empire stretched out space and decentred people from governance, moving from the polis of the small city state to the broad reach of an empire spread across thousands of miles, and it was also therefore a cultural domicide. I think it is fair to say that the West is experiencing something similar and has been for a couple of generations.

There is no such thing as society now; we are the loneliest we have ever been; no one cares5 for elders now, instead they are sent into residential care mainly because we don’t live close enough to them to be able to help in any other way than financially; the housing market is broken so even people who want to lay roots down can’t and renters feel that physical domicide is only a sudden one month notice period away;6 the culture war is escalating; and we have a growing north-south divide. Brexit. The list goes on. We know in a way we are doing it to ourselves. And people are still inviting me round, and three cups of earl grey down still going strong about home, community, creating these for ourselves and our children. Though they know the problem they are floundering for a solution. But how do we create a home? How do we fit this puzzle together?

Sometimes I want to move back to Ledbury, to the place I consider home. It’s there as a red dot on the map. At one point she thought it acceptable too. She wants a house; she needs a home. To me moving to Ledbury is not a big dream, nor a small dream. It is just an easy dream. To me it is home, so imagining that reality is easy. But for her it would be the big dream, because it is finally staking a claim on home. Buying a house is the easy part, rolling the dice on whether that will be home is the hard one. And so we deliberate and think and we find ourselves around at our friends for a couple of pots of rooibos tea talking about moving house, home and community once more.

I sit and listen to people talk about community from a place of not knowing, never having felt they have had it, but wanting it all the same. I hear someone talking about the small town that they grew up in and knowing they had to leave as soon as they could. They complain of the people, the casual racism, the backward parochial mindset, the pace of life and the job opportunities; and I hear the joys of my youth. Let me be clear. I am not celebrating any of these, especially casual racism, but if you hadn’t already worked out, Ledbury is not paradise on earth, the best-kept secret in England, it is a rural working class town with rural working class people. And because they are people they are complicated and because they are complicated they have flaws.

I often wonder if I could move back now and still enjoy it the way I used to. I have changed in the ten years since I left, grown up, realised more about what should be challenged in what people believe. Part of the reason that we haven’t moved there, I think, is that we both know the answer to that question. After all the reason I left in the end was that I noticed friends becoming their fathers and I didn’t see where I fitted into that. And in that realisation, and in the words of the others around the table I realise what they want, what we all want. They want the urban life with the rural backdrop.7 They are caught between the opportunities of people and the tranquility of nature.

Domicide has left most of us with nothing to cling onto apart from the dream of what may be, and we dream those dreams big because partly if you are going to dream, why not, but also because the drumbeat of modernity is individual choice, it is baked into our consciousness. I said earlier that maybe they need smaller dreams; but they don’t need smaller dreams, they are living them. A smaller dream is a simpler choice and they have made theirs, suburbia in one of the most progressive cities in the UK. They have chosen people over place. The networked city with it's host of opportunities, cultures, and variety. Just as there are those who choose school for the same reasons; the networked society in microcosm. And for homeschooling families Bristol a great choice by the way. But this is why every conversation we have about home comes back to community because for them it is always about people. But home can’t be just about people otherwise the kettle wouldn’t be whistling, the pu’er brick being broken and we wouldn’t be still going at it strong.

Would you ever send your children to school? Being self-directed they are free to choose their own education I reply. They look at me like, have you answered my question? So I go again because I know they want a more concrete example. If we were to move to Ledbury I would consider encouraging my children to go to school I say. I have often asked my dad, given I was expelled from school twice would you have done anything differently and he says no. He was a primary school headteacher and he believes that school is not really about knowledge but socialising8 with your peers. And for that reason he wouldn't. My mum wanted to send me to Hereford to a better secondary school, but he persuaded her to send me to the local school with all my friends from the local primary. And it is along the same logic I say that maybe in the circumstances of living in Ledbury I would do the same.

In fact, I am more specific.

If I knew my children were going to live their whole life in Ledbury I would send them, if they were going to leave home at eighteen and move to London I would probably not. But that is an incredible bind, how can we possibly know beforehand.

This conundrum drives at the problem we outlined above, autonomy and relatedness and how to balance them out effectively, or optimise them even. People often ask how do your children socialise? Unschoolers will claim that their kids are out in the community learning being socialised all the time, socialising with homeschool peers, but also in the day shopping, on the bus, in town surrounded by adults being socialised into the real world. Whilst this is true, there is one slight problem with this claim. That if society shuts off a large section of its children for a large period of time, homeschoolers aren’t really out socialising in society in full as society has already been segregated. Now that is not an argument against unschooling as much as it is an argument against schools shutting children out of the rest of life, but it is a fact we must contend with.

In a small town where they are going to live in community for the rest of their days sacrificing some autonomy for the relatedness of a community may be a viable option, hence why I could potentially get on board with the local comprehensive. But that begs the question of if they are going to move to London after they finish school why move to Ledbury in the first place? Why live the tranquility of the rural life? Is tranquility in and of itself a worthy enough value. What do we get out of it? Maybe we don’t want to move to Ledbury in that case; maybe we should stay in Bristol. Maybe that is our smaller dream too? My son was born here, my daughter remembers nothing else. Maybe we will root down here. But when you grow up in the woods of Austria or the orchards of the hinterland then city life stifles you. Home is, after all, where the heart is, is it not?

I can speak for my heart to say that one of the happiest places for me is in the conservatory of the family house with my brother and sister and their families sat around drinking tea or cider as the children play in the middle. I feel at home. Is this about location or about the people? Neuroanthropologist John S. Allen thinks home is as much a cognitive place as a physical one, and that rest, restoration and relationships are at the heart of home for us. For me I think I know that it is about both place and people, but do I know this for a fact: if all the people that I loved moved away from Ledbury would I still entertain moving back? Never. But would I still sign forms as HEREFORDIAN? I think yes.

I asked my partner a few days ago, over the battlefield of small plates of half eaten pasta, a cheddar flecked grater and a stray toy tank, two cold fresh bomber beer bottles sat at opposite ends of the table like sniper’s towers: what is home? A feeling… a consistency, she says. I pick up my sniper’s tower manoeuvering it around the shelled out remains of the conchiglie in the serving dish. It’s peace, she says. It’s also too elusive to be named. A pause… You know, if I die I would die homeless, she says. We move out of the trenches and into the cool peaceful air of the summer night and talk some more, embracing tightly, no longer able to fight back the tears.

Home is a feeling. I think it is a matter of degrees; you can feel somewhere is your home strongly, slightly or not know if you have one at all. We all weave our way through life building an identity, a tapestry of who we are, influenced by both culture and nature. The environment we inhabit is the warp, and the people we meet, the ideas we read, and the moments we share are the threads that we weave onto that tapestry. We are all rich and full and varied individuals, but, it seems to me in contemporary life, that some of us know home and some of us don’t.

Home, I believe, is a feeling which comes from the consistency of weaving threads into the same part of that tapestry, overlaying thread after thread, building a tactile impasto identity rooted in place rather than a thin veneer spread out across a large canvas. Sometimes we move house and start again in another part of the tapestry, sometimes our experiences require us to set aside the colours of the most beautiful dawn and weave in greys of ash and lead as we deal with grief or sadness or hurt. What home is is in a sense decided by us, it is unique to our personalities and experiences. To some the tightly constrained physical space of the family house is home, to others the village of thirty houses and the surrounding fields. Maybe you threaded enough threads across a whole city in your youth that it is home to you. I don’t want to bias this metaphor with my own experiences of secure place making in one location and so I am willing to entertain that home could be a friendship group bound not by deepening of threads laid on top of each other but by the reds of love, roses, blush and strawberry, intermingled with the dark crimson wines of rage, and pulled taut by the reconciliatory threads of a deep burgundy love, all stretched across a wider space, but on whose thick woollen yarns your mind easily traverses, a rope bridge of place spread between brothers from different mothers.

Home is the place where you feel at peace, where the threads feel full, colorful and alive, because your identity is at peace. It is, I think, about people and place. Glen Coulthard, an indigenous Canadian and professor, says this about place.

We are always kind of embedded and constituted by what’s around us… I’m nothing; I’m just a product of the messy relationships that have formed me over time… we have tended to think of these relationships as anthropocentric. But we’re also shaped by the other-than-human relations we’re thrown into, including relationships to place and land itself, and that can have an effect on our perspective, it can shape our normativity or what we think is right or wrong.

The tapestry metaphor of home I hope recognises that the threads of people and culture have to be embedded into place and land. The reason that Ledbury seems so alluring to her, and that half of the red dots on the map above seem so inviting to both of us is that they replicate something deep within: those relationships to place and land that we grew up with, the rural, tree adorned, fields of our youth, the woods of exploration and play and freedom. These pastoral scenes are a powerful replication of meaning to both of us. And whilst Herefordshire still seems idyllic and comforting to me and Austria does not to her, the pattern language of childhood and nature is firmly rooted in both our psyches.

We need nature; we both find city life hectic in comparison to the childhood towns we grew up in. Furthermore, we both think that children need nature when growing up. Wordsworth said the path from childhood to adulthood runs not from former to latter but through nature itself. However, our children spend 15 hours a week in a learning community in a woods, we share milking goats, try to get into the countryside for walks, to forage and then make food together.

To some extent they have the access they want and need. Or, from another point of view, an unschooling one, who are we to say that they don’t. One of the key takeaways I took from the book Kith is that children’s needs for spaces to make dens and play in nature is inherent, but the spaces that they need to do so need not be large. I think it is hard as an adult to see the possibilities that a seemingly tiny slice of nature gives seen through a child’s gaze. When my daughter was learning to walk we would walk to a farm shop with a little playpark almost every day. We had to traverse a tiny copse that I could walk through in thirty seconds, but she often managed to spend thirty minutes voyaging through. The complexity of space-time bends not only in the vacuum between planets but also between generations of the same family in the shade and leaf litter of an old oak. And it is that mismatch in perspective that gets at the root of how we as unschoolers must relate to the question of home.

To be home is not a verb followed by a noun. To be home is a verb in itself; we are pigeons as much as people, we home.9 My favourite walk in the world is a circular affair from Ledbury over the hill through the unmanaged coppice of hazel with pine overstory down into Eastnor, through the cricket pitch I played at and past the castle and then back home.

The field a husky I was left with worried some sheep: Photo by Simon Burchett on Unsplash

There are locals here who have a lineage that stretches back generations who have ancestors who also would have walked this same walk, maybe it was as far from their house as they ever got. But if we stretch it back far enough into deeper time we see that though they may have only walked village to village their ancestry has walked from valley to valley. Ledbury to Eastnor for them, but from the Rift Valley out of Africa, through Europe and down past the orchards into this sleepy hollow on the edge of England. Because to be home is not to arrive and remain static. It’s to participate. Each generation will have homed on their way from there to here. To be home is to be active. To participate in the conversation of life in a specific place; holding conversation in the conservatory with the family is not to be home, but to keep on threading into the tapestry, making it more home in the process.

This activeness of making and creating home all the time gets at the difficulty for the unschooler in these times of domicide. I often hear adults talking about moving to another city when they have children of a similar age to ours saying that their children will be ok, children are so resilient aren’t they. And in writing this I wonder if that is really true. As I wrote about recently the metaphors we use are important to help us frame our thinking, but can also be dangerous to our practice and in the context of a metaphor of home as meaning making, an active process, are children really resilient, or are they maybe adaptive?

Resilience implies an ability to withstand a shock from outside a system, whilst adaptive seems much more processual. In meaning making there is nothing to recover from, nothing outside of the system. The making of meaning, the activity of homing, is an ongoing participatory process. Unschoolers believe that children should take an active part in their own education; self-direct their own learning. Unschooling should also therefore allow an active participation of children in the decision of meaning making, of creating home, because they are already weaving their tapestry together.

Resilience implies that uprooting a family to another location is a pause around which meaning is made, but I think that the shock is as part of the process as anything else. Conversations with my partner seem to lead me to think that if you move around enough the shocks could even become more meaningful than the places.

Therefore to unschool our children is to allow them the same rights10 as us in the decision making process, to invite them into the conversation, to trust11 them in the process. To recognise that they are already creating an identity of people, culture, place and land, and that it is not on us to control how they weave their tapestry. Alison Gopnik has written how parenting should be less carpenter and more gardener, less moulding and more tending; or, less weaver and more haberdashery.

This essay has no answers here, either for the concept of home or unschooling. This metaphor guides us not to a solution, it’s a map without a compass, a guide to the contours of the hills without the paths inscribed. Home as an active process, a tapestry that is always being weaved, tells us that we shouldn’t forget that we are always creating home in some way, that home is as much cognitive as physical, as much emotional as practical. Place is clearly deeply important to us, but so are people for it is people who animate place, be they your ancestors or your contemporaries.

As to unschooling again there is no answer. Decisions about meaning making, about home, should involve children. Children are real people too and though they are younger and with less life experience, the life experience they do have pertains precisely to their life and that should be a value in of itself. It is true that they do not have as much knowledge as adults, but then again knowledge is not wisdom, and even if we as adults can claim to be wise, wisdom should always remain humble to the fresh eyes wisdom of the young.

Those two letters popped through the door whilst we were out at the shops. My daughter had ridden her bike and it being extremely hot had taken off her shirt which did her no favours at all when she fell off. Tears wobbled down her cheeks as she had down the hill until they reached her chin and gravity claimed them as it had her from her saddle. She insisted that she couldn’t move as her grazed chest was in too much pain and that I carry her home on my shoulders.

Thus proceeded the ludicrous carnival of carrying her and her bike fifty yards, going back for her toddler brother who was now “injured” too simply from the injustice of having not been injured as well, crying that he couldn’t also be cared for as she was. When we sojourned together, it was only briefly before I picked her up again and proceeded along in a two steps forward one step back kind of way. I have carried both my children on my shoulders since forever so the load was manageable but the humid heat of the hottest day ever known in Old Blighty was taking its toll.12

She used to live on my shoulders, at age three could fall asleep not holding on and I wouldn’t have to hold her legs or feet either and we could walk together like that for miles, with her shifting her weight in her sleep but never falling. Halfway home she realised both that she could roll most of the way home on her bike and kindly spare me of half my load and that my shoulders had fulfilled their role as emotional support, an upside-down weighted comfort blanket if you will.

As I sat at the table with the open envelopes I thought about the act of carrying a seven year old, the weight of a child that very soon will likely climb on my shoulders for the last time. I reminisced about when she was two and still breastfed and trapped her fingers in the door and howling in pain sought not the universal symbol of comfort, the breast, but climbed up on my lap as I sat on the sofa and on to my shoulders to suckle on them instead. As I tossed the electoral request form in the bin I gazed out the window at the trampolines, footballs, and balance bikes, and watched her shed her pants and jump into the paddling pool screaming in delight and realised that as she sits on my shoulders, she is making meaning, warping them with her weight whilst weaving around them with her fingers. Home is the scarf of meaning she wraps around my neck, and I realise that as she actively does this, if I am actively listening, I can hear the fresh eyed wisdom of the young saying, we are home.

As someone who doesn’t drive but is aware of the rising cost of fuel I am not sure if this metaphor still holds, or is likely to hold if you read this a month or two after I publish it.

This was an error that I left in when I was rereading through as I found it poetic; it should obviously read universe.

Not even one worthy enough for my parents to talk about at dinner parties, but at that stage the fact that I had even gone was worthy enough for them to talk about.

One person did start to experiment with intentional communities but did downgrade their initial passion for co-starting one to visiting one to see what they were like.

In both senses of the word sadly.

I have watched a friend go through this recently as being asked to leave their rented property they have found they can no longer afford to live in Bristol and so have had to move to Gloucester, losing both house and home in one go.

I’ve often said that I often wish I could have been born in Ledbury and grown up a proper Herefordian knowing nothing else, never feeling that itch to move and scratching it and blissfully living out the rest of my days in the sleepy market town. I feel the Tao Te Ching gets at this idea when it says something along the lines of not knowing is true knowledge.

It is fair to say we have different opinions on what socialising means and looks like and also what is healthy but it is an interesting perspective from a teacher. His school was fairly radical in that it did away with most of the idea of a curriculum of separate subjects and taught most of it through one big project that took a whole term to complete.

Here I recommend this article and this particular quote by fellow Social Club member What, Bang, which he released after I had written this piece but had not yet finished editing it and seems to drive at the same thing.

It is important and impossible to remember that there are no things. But if there were, there would be no nouns. Nouns are verbs moving very, very slowly. Or: all nouns are gerunds.

It is important to recognise here that rights does not imply equality in having a say in the outcome. They have the right to voice their opinion and their opinion to be taken seriously. There might be greater factors impacting other people than them. A half hour move might mean that a parent’s commute is reduced by half an hour everyday, but a child’s journey to gymnastics club is increased by half an hour once a week; these may feel equally as impactful to the person and should be honoured as such, but the decision must be more nuanced to notice that actually one is more effecting than the other. Ideally we would be working in the realm of consent and sociocracy as we discuss this.

Every post I make it seems touches on trust as the bedrock of unschooling.

It genuinely was a scorchingly hot day in the top twenty hottest days on record.